Shortly after the second wave of COVID-19 hit Russia, I went to Ponarth to learn more about one of the two parts of old Königsberg that survived the Second World War. The less is left of the spirit of Ponarth, the more tensions over Kaliningrad’s past bocomes visible.

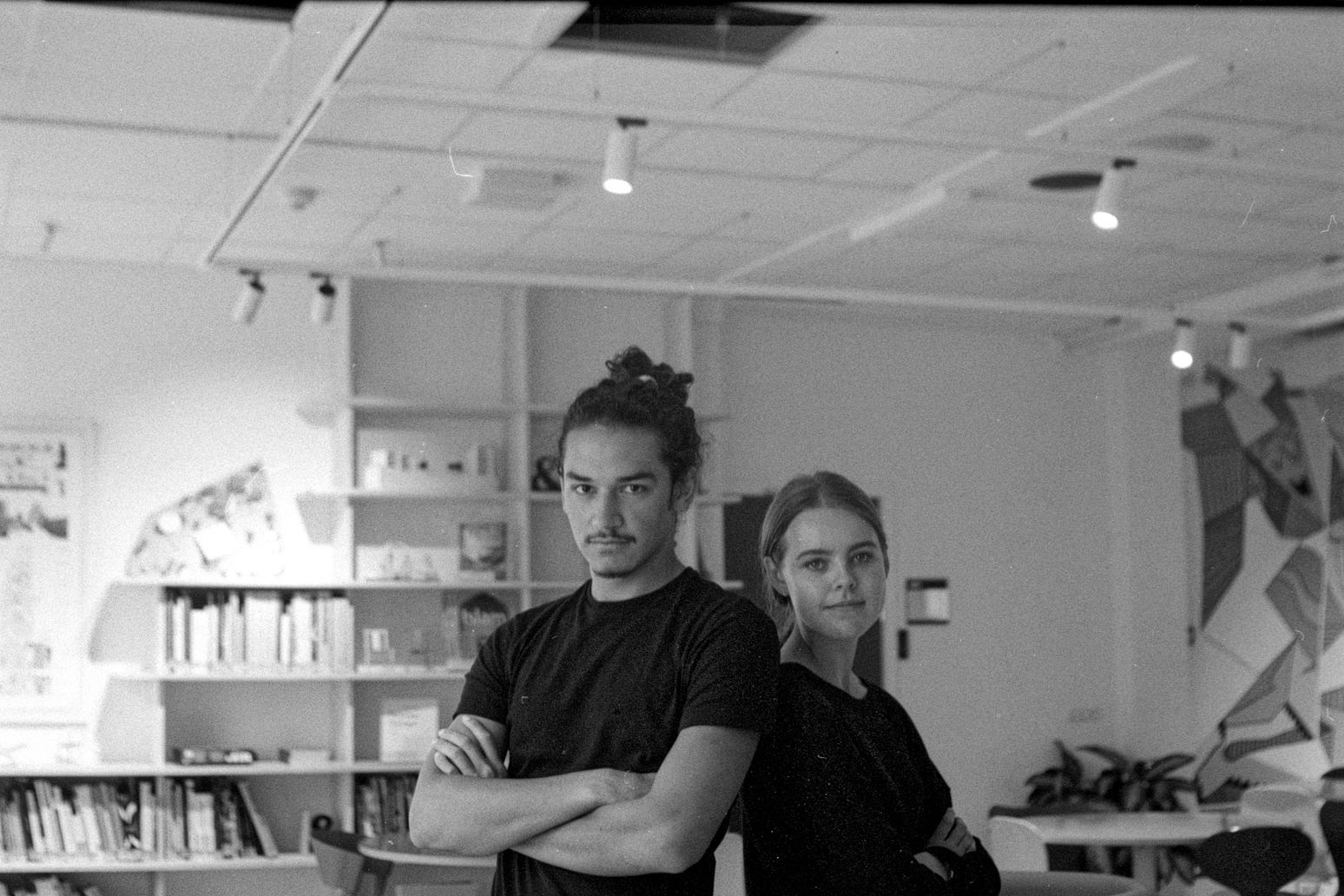

This is a revised version of the story I published on 35mmc.com in June 2021. I want to remind it because of some other thoughts on Ponarth I intend to share soon. I took all photos featured in this story.

Ponarth, contrary to Amalienau/Hufen, was not held in high esteem. There were neither elegant fin-de-siècle villas nor representative public buildings there that Soviet military and civilian officials could take into possession. Yet Ponarth has something else to offer — the intimacy of an area away from the city centre where contrasts between the pre-war East Prussian and the post-war Soviet pasts are deeper, more pronounced and yet more harmonically embedded into everyday life of the district’s dwellers.

Ponarth has been separated from the rest of the city by the Pregel River together with its flood waters and meadows it creates. It flows through Kaliningrad Oblast and finds its way to the Vistula Lagoon just outside of Kaliningrad. It sounds straightforward but the Pregel is a peculiar and capricious river. It starts where two other streams — Angerapp and Alle — join. At some point along the way, the current becomes so strong and the amount of water so large that the Pregel bifurcates into the Pregel proper and the Deime. Yet it was still not enough to keep the element at bay. Just outside of Kaliningrad, water flow gets so immense that the river meanders, creating islands and meadows so swampy that they remain largely uninhabited, serving only as summer houses and fishing spots.

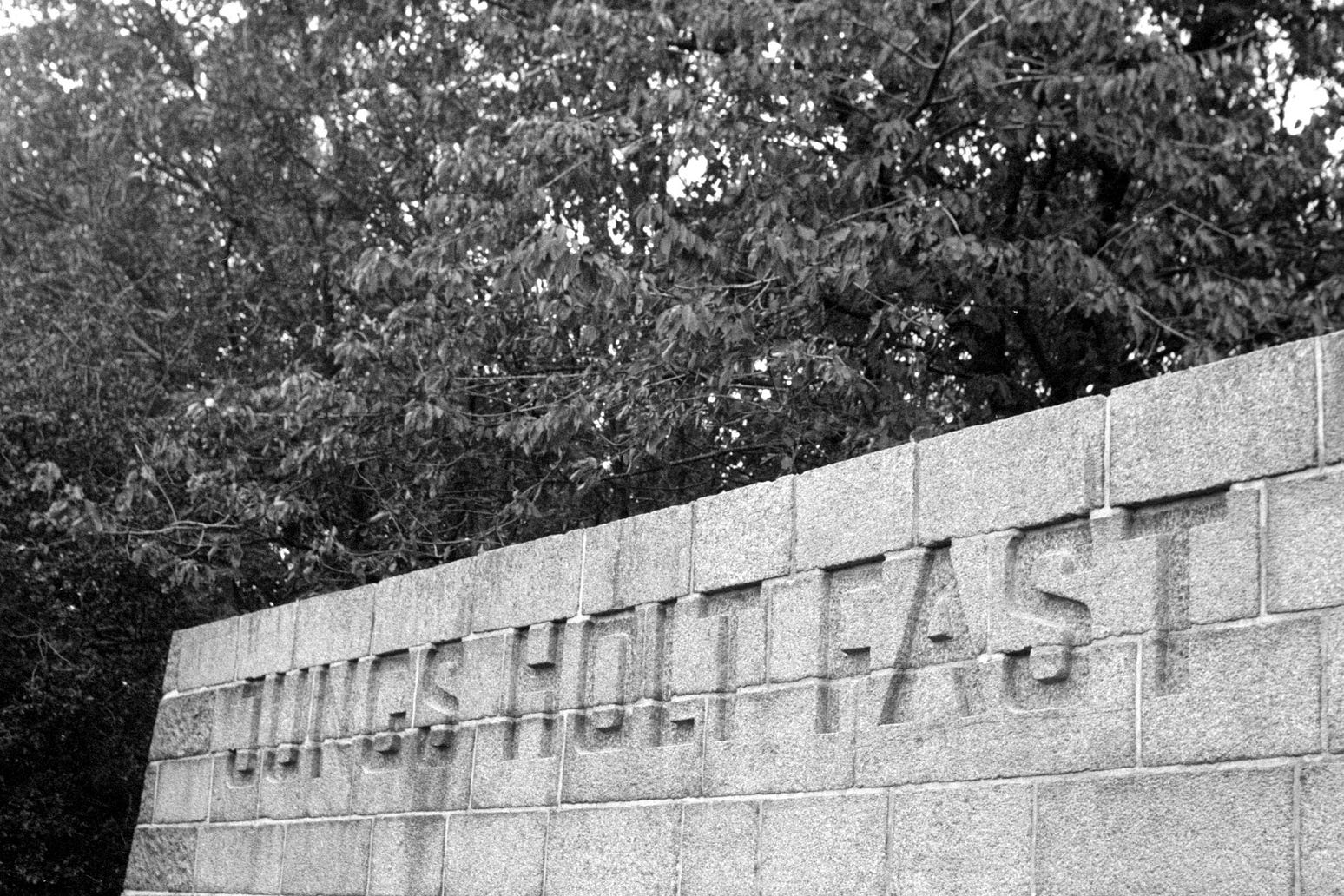

The Pregel has behaved this way for centuries. Its wildness and capriciousness probably got envisaged in the name of an old Prussian settlement which later became a village and, subsequently, a neighbourhood within Königsberg — Ponarth. The name is believed to mean either behind the edge or diving, submerging, whirling. In both cases, it clearly refers to the Pregel and its wetlands which still separate this part of Kaliningrad from the historic down-town.

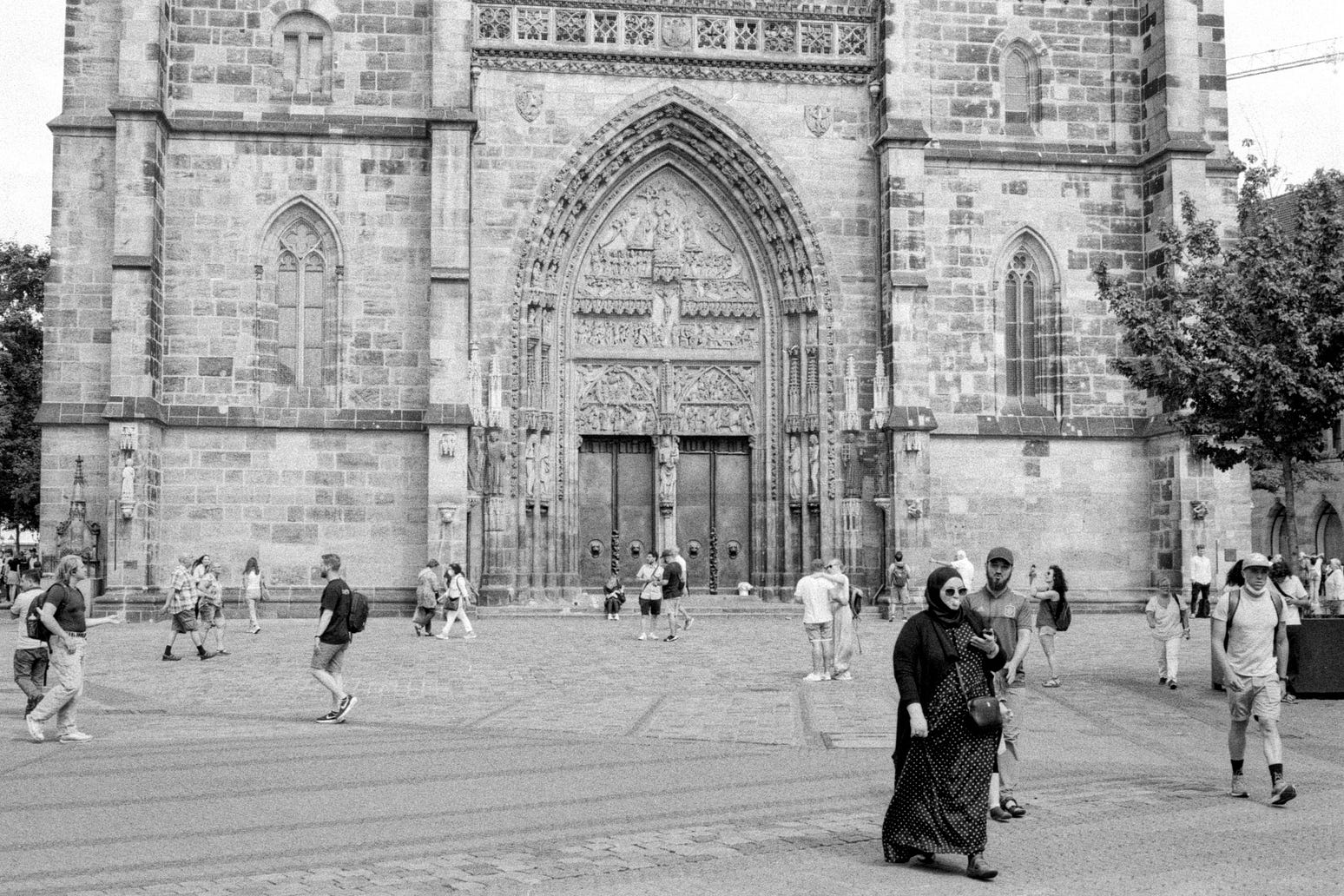

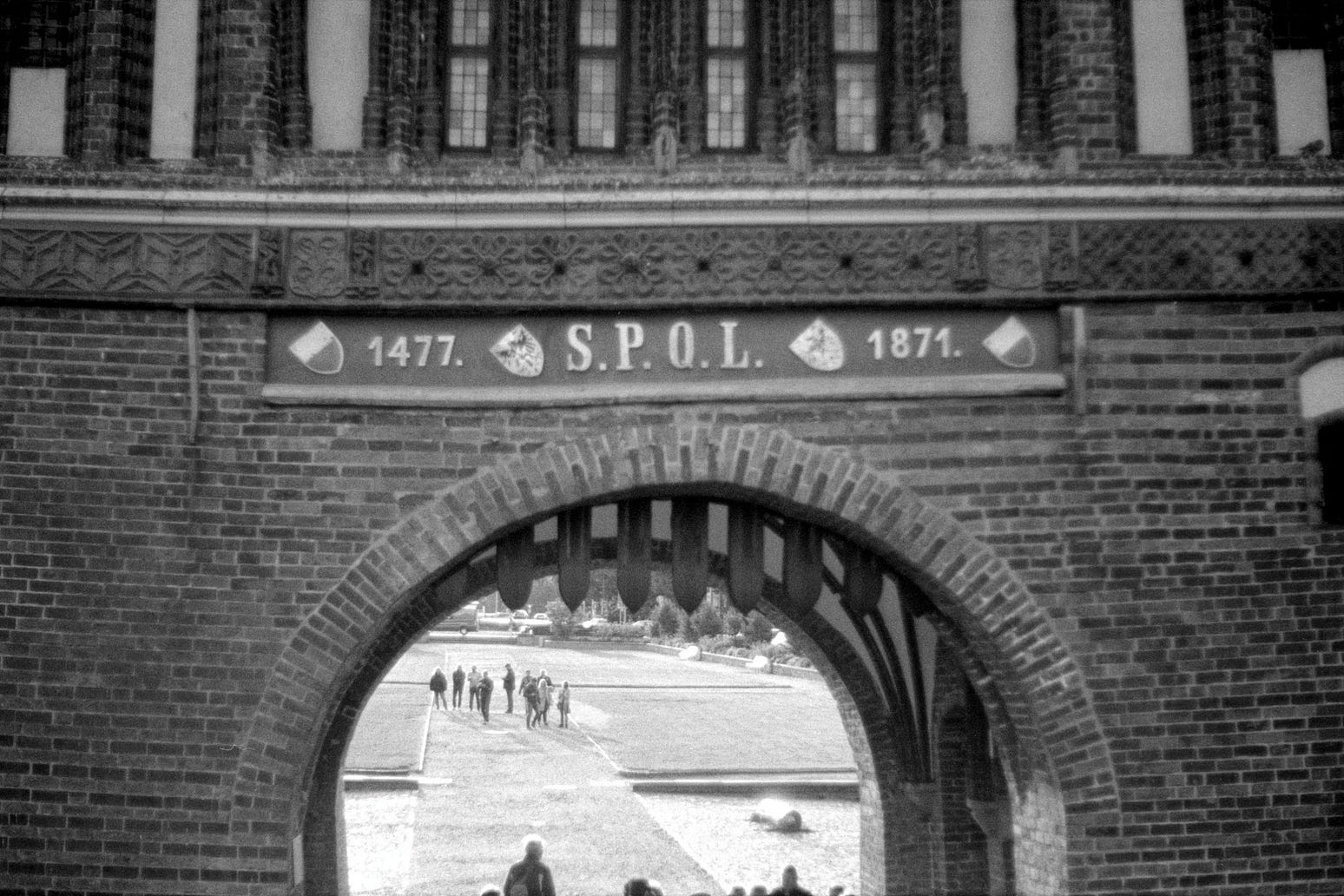

Ponarth’s golden age began in mid-19th century along with advancing industrialisation and construction of the East Prussian Railway, connecting Berlin with Königsberg. The rural village quickly transformed into a town with a bourgeois park, a neo-Gothic church, a sports club, and a brewery. Especially the latter became main stimulus for the settlement’s growth. Founded in 1849, the brewery produced over 100,000 tons of beer a year by the end of the century, making it was famous across all Germany.

Such mass-scale production required manpower which an ordinary village could not provide. In late 19th century, Ponarth’s became a town in its own right with over 8,000 inhabitants. Construction of houses that followed the population boom blended it into Königsberg proper and, starting from 1905, Ponarth functioned as a suburban district of East Prussia’s capital. It has been busy and lively every since, always retaining a colouring of its own.

The Second World War left Ponarth damaged, but not destroyed, similarly to the west of Königsberg (usually referred to as Amalienau or Hufen). Most importantly, the district’s main factories continued to function. As military officers and clerks moved in comfortable villas and semi-detached houses of Hufen, so did industrial workers in poorer dwellings and brick houses of Ponarth. This made Ponarth repopulate quickly with newcomers from all over the Soviet Union even though some factory equipment was disassembled and moved to other parts of the country as reparation for war losses. In 1947, two years after the war had ended and a year after Königsberg was renamed into Kaliningrad, Ponarth got incorporated into the newly established Baltiyskiy Rayon (Baltic District).

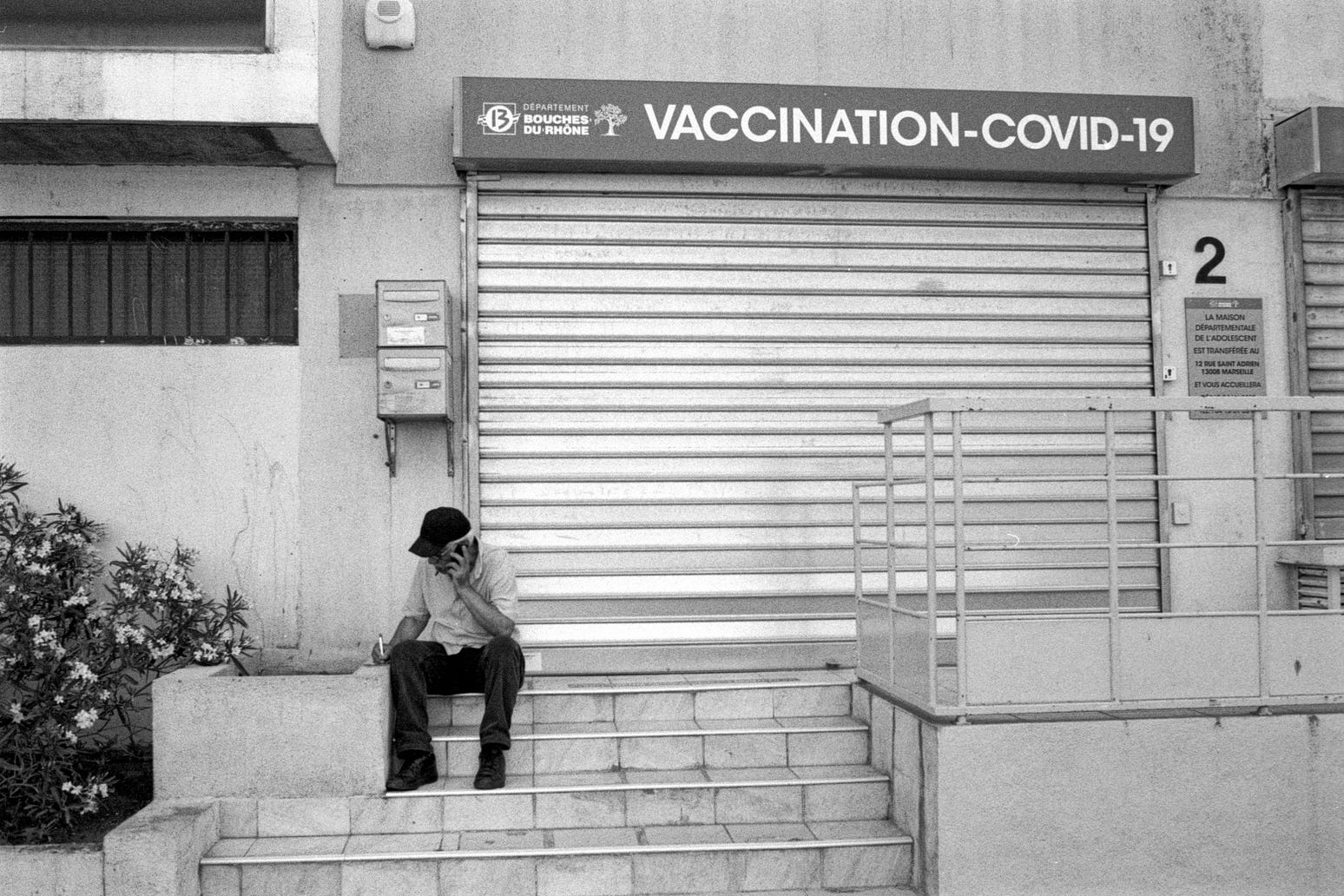

New inhabitants did not feel at home in former East Prussian, portrayed as outpost of German militarism and nest of fascist invaders. It took them decades to start domesticating the space. During this time, gradual decay of the Soviet economic model felt even more painful in a remote corner of the empire where wartime damages had never been fully repaired. Already in post-Soviet Kaliningrad, the name Baltrayon became a local synonym for shabbiness and roughness. Some people even called it ‘the bear’s corner’, advising not to go there without a clear reason.

At the same time, Ponarth existed as a symbol of old, better times, free from the worries of today although it was largely a prefigurative illusion. Whereas Baltrayon was liquidated in 2009 as a result of administrative reform, Kaliningraders have kept memory of Ponarth’s charming distinctiveness.

Most people who know something about the history of Kaliningrad/Königsberg and East Prussia remember the Zhigulyovskoye beer which continued the pre-war traditions of Brauerei Ponarth. Buildings of the historic brewery are still there although now a large part of them is in very poor condition and is unable to serve its purpose. It would not be easy to achieve anyway since memory politics in Russia have narrowed the space for free use of pre-1945 references. This is something I will address in my second post about Ponarth where I revisit my own thoughts on the district and its dwellers.

Is it justified to say that the spirit of Ponarth still wanders around the district? On one hand, the neighbourhood has been part of Soviet/Russian Kaliningrad for over 75 years. Its inhabitants, street names and many other things have altered since 1945, resulting in many elements of the pre-war material and non-material culture sinking into oblivion. On the other hand, the memory of Ponarth, its rich history and charm not only has survived but has also been cherished by many contemporary Kaliningraders. Plus, even they keep using the old name. At least in this sense Ponarth has withstood the test of time.

What is bothering is the shrinking space for different narratives on the past in contemporary Russia. With the war in Ukraine continuing and Russian economy suffering from the Kremlin’s policies, the authorities are using history to draw people’s attention to non-material issues and distract them from the actual problems. In today’s Kaliningrad Oblast, tales of Russia’s military glory over the centuries are dominating. It is a bad sign for inclusive, community-building memory about the past of places such as Ponarth.