It is a story of how reigniting the flame of shooting film made me appreciate the late 1970s West German and Japanese design wonder. It is so compact and sleek that no matter what I need to bring to frequent research and teaching trips, there will always be space for my Contax 139 Quartz.

I took all photos featured in this story. Check my webpage for more content. You can also buy me film to keep my work going.

I recently revisited and revised my story on Kaliningrad’s Ponarth district, which I had explored back in 2020 when I had been posted to Russia as a diplomat for Poland. It was a time when my interest in analogue photography spiked, possibly because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions we all suffered from. To satisfy my aesthetic needs, I sought more unpredictability and excitement while taking more control and responsibility of the creative process. Film cameras fitted perfectly in this picture (no pun intended).

I decided to go for a Minolta X-570, which I found on eBay in a great condition and for a decent price. I do not own this camera any more, but I still value its good performance and the ease of use. It felt, however, too plasticky and did not give me the kind of pleasant, tactile experience I was looking for. As much as the X-570 was a good way of kicking off with a more thoughtful and joyful analogue everyday shooting, it left me unsatisfied. I convinced myself I needed something more and something different.

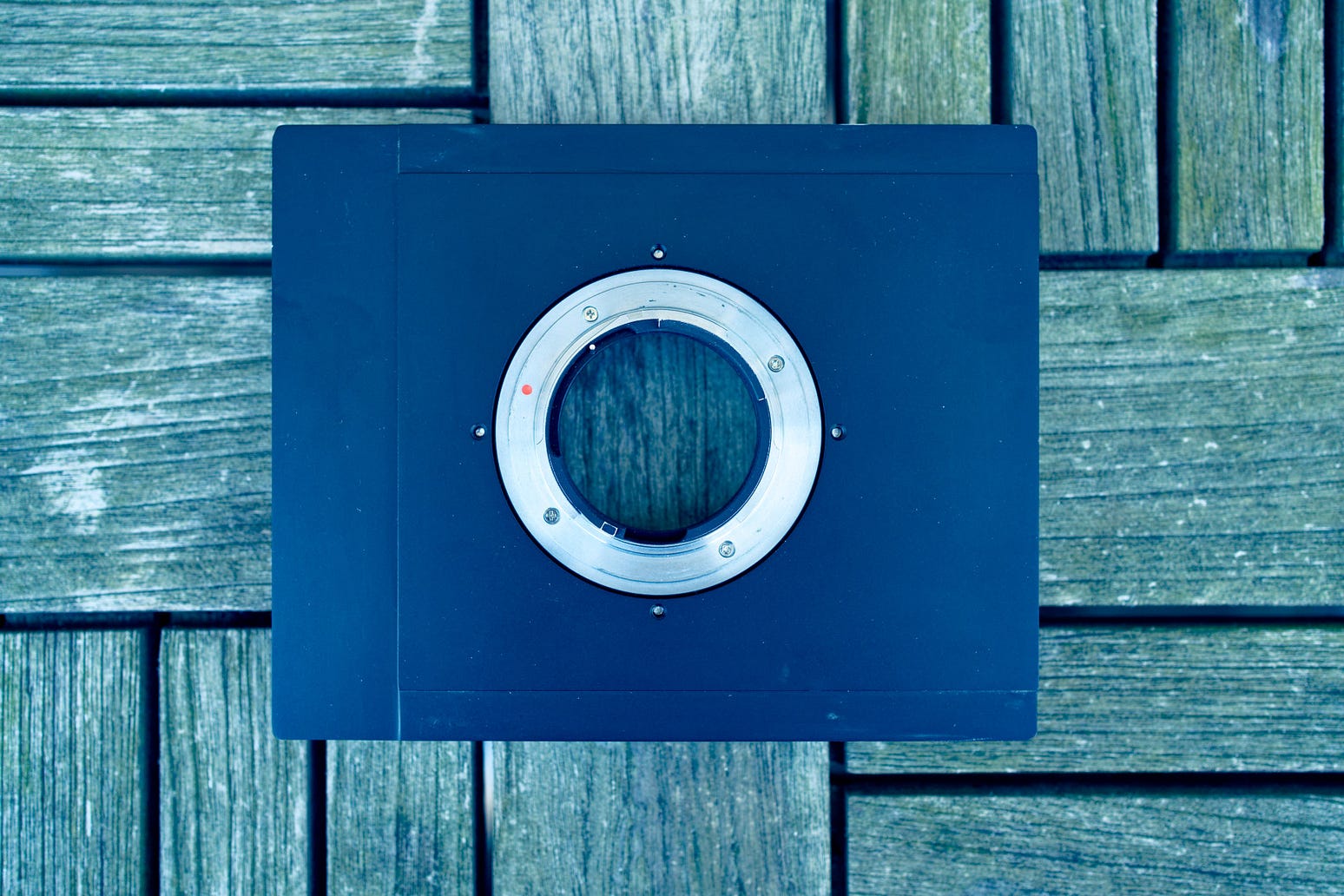

This is the part when you might think: so he got himself the Contax 139 Quartz and he will finally get to the point. You are half-right. After parting with the X-570, I first went for a camera that I still own and love but find slightly oversized for my light-packing travels. It was a Contax 167 MT, bought at eBay from a seller in Germany who told me that this piece of Western capitalist technology had been bought by an university in communist East Germany to take high-quality macro shots. Indeed, the Carl Zeiss 60mm f/2.8 Planar that came along, as well as a custom back plate it made this Cold War story plausible.

I was impressed with the design and build quality of the set. No wonder it was developed in cooperation with Porsche Design Studio: sturdy but sleek, elegant but toned-down, with sharp lines but ergonomic. Very quick shutter release times (up to 1/4,000s) and electronic control over them made it easy to shoot quickly for an analogue camera while not losing the joy of manual focus and everything that follows. Yet something was still lacking, although I could not put my finger on it. Bear with me and show patience, just as I did.

At first, I began looking for different lenses. The 60mm Planar is bulky and heavy, thus not very inconspicuous when shooting street life. I found a 50mm f/1.4 Planar in wonderful shape and there I had it — I developed a typical gear acquisition syndrome, or GAS. I loved the feel of those lenses on my 167 MT also because it came as a cognitive shock that they were produced at the same time as Prakticas in the German Democratic Republic, which I used to shoot with as a teenager. Back then, they were superior to the Soviet Zenits in every single way. When compared to 35mm Contaxes, however, the difference in technological advancement and craftwork made me flabbergasted.

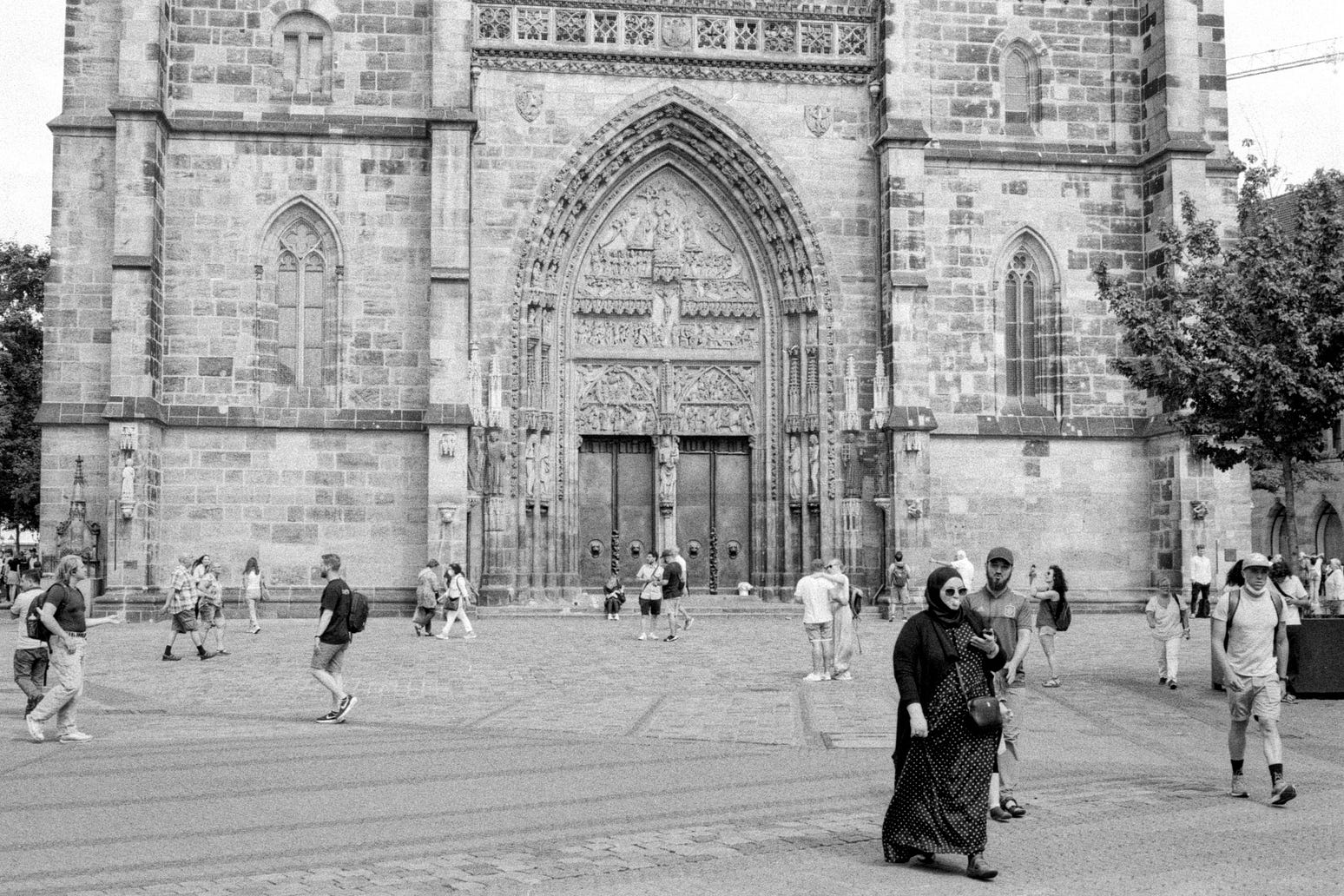

I then gladly heeded the self-proclaimed need for more gear and went on looking for a 35mm lens. It was the time after I had moved to Denmark and took a lot of photos around me just to get acquainted with my new place of living. As I moved from diplomacy to academia, my professional activity requires me to travel even more frequently. These are usually short trips with my students or to attend conferences and workshops. I wanted to make most of these voyages, also to show my students the joys of shooting film. They had the Prakticas, but what was I supposed to get?

I quickly discovered how small of a market Denmark was in terms of analogue photographic gear. It was not an easy task to find what I wanted unless I wanted to risk bringing something over from Japan and paying taxes and customs.

My patience paid off when an amateur photographer and a fashion enthusiast offered the much wanted 35mm f/2.8 Distagon lens in a very good condition. It came with strings attached, though, as it was accompanied by a 50mm f/1.7 Planar and a Contax 139 Quartz. I was not entirely happy with having to buy a whole set but hey, what about the everlasting presence of GAS? My explanation back then was that I could always sell the extra body and even get rid of the extra 50mm lens, especially that I already owned its faster version.

Little did I think about the consequences of this move. At first, I almost frowned upon the 139 Quartz. Small, with shutter speeds ranging only up to 1/1000s, no automatic film advancement, everything controlled with knobs. It felt like a step back when I used it alongside the 167 MT. I took both bodies to a couple of road trips. Since space and weight were of no importance, I frowned upon the 139 Quartz. It was an older, slower and poorer brother of my fancy East-German-university-macro camera. How very judgemental of me.

But then, something clicked in my head and made me connect the oh-how-disappointed-I-am-with-you 157 Quartz body to the 45mm Tessar. The result was thrilling. Never before had I seen an equally handsome, minuscule connection of metal in black matte finish and delicate leatherette of this 1979 camera. I fell in love so much so that I started displaying the set on my desk. It was way later then that I discovered that I had been charmed by the intentional effect the creators of the 139 Quartz had sought to achieve: an interchangeable lens camera so small that it can fit into every bag and rucksack without making any rotten compromises.

Size aside, what is it that makes this camera marvellous in my eyes? Wake me up in the middle of the night, ask me this question, and the answer will always be the same: ease of use. It is mostly because it has aperture priority mode. After selecting the desired value on the lens, you can look into the viewfinder, press a button with your index finger, and a little red LED will automatically show you the correct shutter time. You can even engage your pinkie to check the depth of field when focusing and composing the frame.

Although the 45mm Tessar is a small lens, it is still comfortable to use. The aperture ring is large and tactile enough to operate it intuitively. In the beginning, I only struggled a bit with the focussing ring. It sits close to the aperture ring and the lens’ front, which makes it rather narrow. It thus requires some thoughtfulness in everyday use. After some time, however, one can get used to this trade-off as it benefits the overall small form factor of the Tessar.

It still impresses me that the built-in light meter is accurate and, although there are no different metering modes, one needs to try hard to produce an ill-exposed picture using this semi-automatic mode. It happened to me only once and it was entirely my fault: I was photographing a black-haired person wearing dark clothes against a very sunny background. I should have used the AE lock and the exposure compensation system, which Contax engineers included in this wonderful product.

You can also use a fully manual mode and set the desired shutter time yourself. After using the same button, the camera will show you the time you selected and the time it would choose for taking the picture. If they differ, the former is constant, while the latter flashes. If the values align, there is only one blinking LED. There is also the OVER indicator for overexposed subjects. How intuitive, how convenient!

Otherwise, all the dials and knobs on the camera are manual. You need them to set the ISO of your film (no DX coding, sadly), the mentioned shutter time (from 1/1000s all the way up to 1s, B mode and X for flash synchronisation at 1/100s), AE lock with exposure compensation dial (+/- 2 EV), as well as quartz self-timer set to 10 seconds. Join-the-picture became so easy that it gave the name to the whole camera.

The biggest pleasure I take from using the 139 Quartz is its shutter sound. It is toned down and soft yet still audible and decisive. Since there is no automatic film advance, no other sounds follow the shutter. It is way more suitable for street photography or other environments in which too much camera noise can be disturbing.

Does this camera have drawbacks? Naturally, but I prefer to call them trade-offs as they mostly come from the compact form factor rather than design flaws. Because of how small it is, it does not feel as good in my hand as the 167 MT. There is no pronounced grip which my long fingers usually need to get a steady control of the photo-taking process. Since the 139 MT is lightweight (slightly over 600 grams), it does not matter most of the time but in low light conditions, not being able to grasp the camera decisively can be somewhat bothering.

Another thing is the focusing process, slightly impacted by the rather dark viewfinder. It makes you feel that although Contax 139 Quartz was a significant step forward in so many different aspects, it still suffered from the same hurdle that most models devoted to amateur photographers struggled with at that time. It was only with the arrival of the Aria that Contax addressed this issue in a satisfactory way.

Yet my most serious reservation about this camera in reality pertains mostly to myself. Throughout this whole process, I fear I might have demonstrated consumerist greed and impatience closely related to intellectual sluggishness. You might think I am harsh on myself, but believe me, I thought the above statement through. I should have spent more time researching different options, looking for real user opinions and weighing my priorities. I could have also stuck to my Minolta, enjoying its earnestness and straightforwardness, albeit packed in a slightly inferior body.

In the end, however, this self-critique should be taken with a grain of sold. Yes, I might have spent a bit of extra money, but I did not buy new things. Instead, I went for items that were produced many years ago. By making sure they will continue to function, I extended their lifespan and put them to a, hopefully, good use. Thus, I want to think that the environment was not substantially hurt by my unconscious search for a camera I can take anywhere I go. I even biked to pick up the 139 Quartz, bringing back a few hundred burnt calories and an piece of engineering capable of giving joy to me and to those who I photograph.