Back in 2022, I was still at the beginning of my work with U.S. students coming to Denmark. When a colleague of mine at DIS Study Abroad suggested I could accompany her and her summer class to Marseille, I did not hesitate for a second. I immediately sensed this study tour would bring opportunities to add new items to my teaching toolbox and experience a place which history is relevant on both sides of the Northern Atlantic. Naturally, none of this could happen without the analogue angle.

It was a summer course my colleague designed to be special in many ways. Its focus were the discourses of colonisation and de-colonisation — a topic sensitive for millions of individuals and for whole societies, especially given the heated debate over many nations’ grim colonial past. Coming to terms with it is a long, difficult and oftentimes painful, affecting many areas societal life.

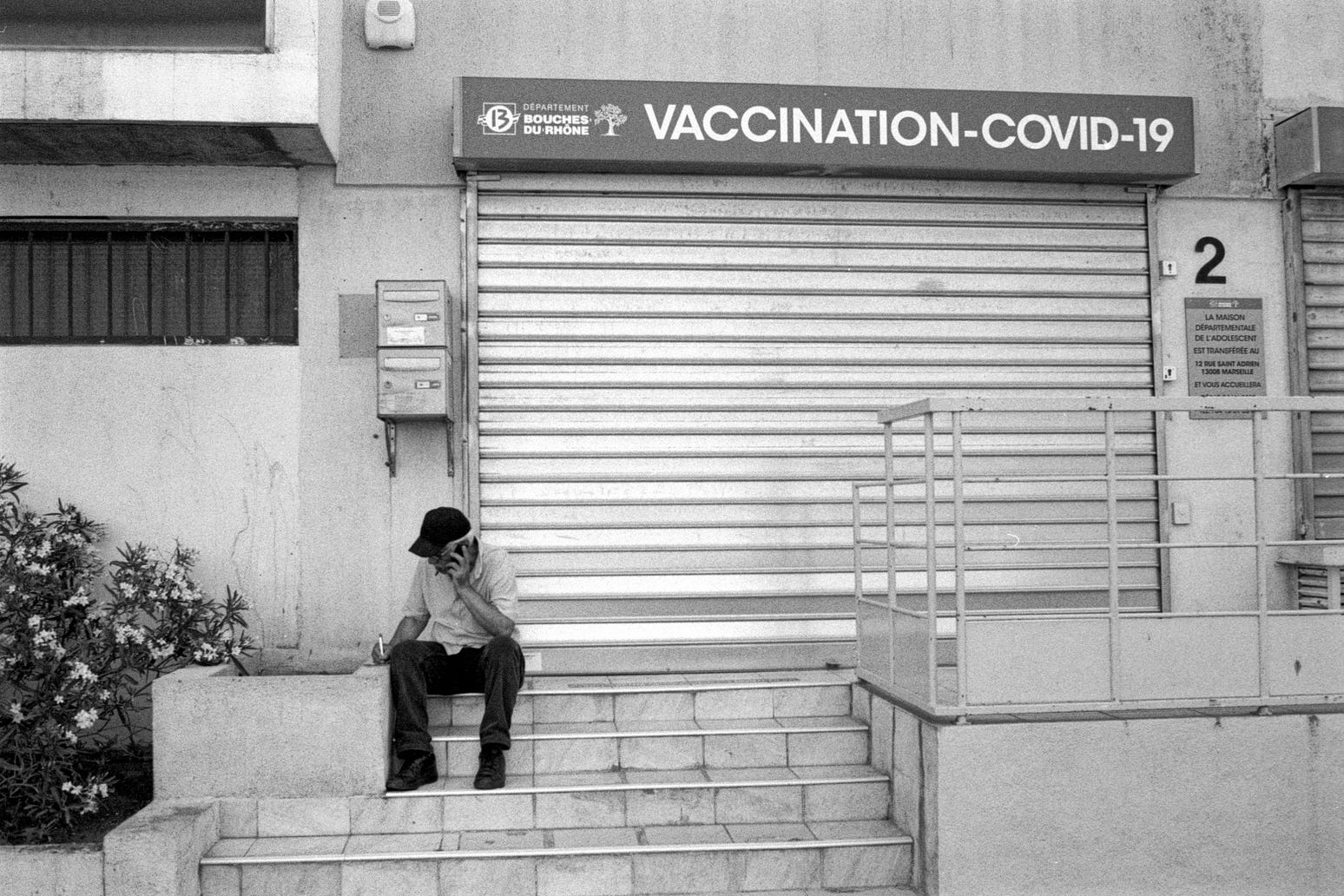

As far as a direct contemporary angle is concerned, we were going to a city that, willingly or unwillingly, had been standing in the middle of a sharp political debate in France on migration and integration, or rather the latter’s fiasco, as well as the tensions that race and religion have generated over the centuries not least because of Europe’s brutal exploitation of peoples on other continents. Talking about these processes sounds like walking on a minefield and, indeed, it can become one when discussing it without sufficient knowledge, sensitivity and empathy. For me, most of my professional life dealing with Central and Eastern European affairs, going to Marseilles with a class focused on colonialism was an opportunity to step out of my comfort zone and gain new perspectives.

What made the trip even more challenging was the fact that our students came from a country where polarisation levels had been reaching new heights every time one thought it could not get any worse. Many recent events have shown how different shades of xenophobia and other forms of social prejudice can lead to violent events. Heated public debates, often taking the form of accusations, shaming and blaming instead of a genuine dialogue, had not made reconciliation any easier.

Marseilles presented all these challenges in the European context. To my relief, it did so in a uniquely charming and awe-inspiring way, not free from tensions but with clear and tangible proof that meaningful dialogue is possible. As the largest maritime gateway to France, it is home to Catholics, Muslims, Jews, Orthodox Armenians and Vietnamese. Around a fourth of the city’s population was born abroad, often coming from former French colonies and Algeria, which before independence formed France’s three departments.

Unlike Paris, where immigrants live in the suburbs and the satellite towns, Marseilles down-town bustles with different languages and cultures of its inhabitants. French right-wing populists present it as a sign of the decline of France as we know it and the biggest threat to the nation’s centuries-long culture and the post-1789 secular state. After all, the French national anthem, tightly connected with defending the achievements of the Revolution, takes its name from Marseilles.

Apart from making sure that our students actively participate in the study tour activities, I tried to make the most of my spare time. I searched for a neighbourhood where, while being close to the city centre and the hotel we were staying at, I could capture at least a small part of Marseilles’s genius loci. By a stroke of luck, I ended up in Le Panier, the city’s oldest and arguably most charming district.

When taking the countless stairs up and down, I did not realise I was traversing more than 2,500 years of Marseilles’s continuous development. Greek merchants picked this hilly peninsula for their ancient emporium, Massalia. It took only two centuries for it to become one of major trading centres in the whole of the Mediterranean. The Greek made it easy for the Romans to build on this astonishing success. Do you remember Asterix the Legionary? In search of Tragicomix, the two Gauls went nowhere else than Roman Massilia. Already then, Goscinny and Uderzo portrayed it as multi-ethnic and multicultural.

My interest in Panier became even bigger when we took the students for walk with a local guide, Martin. An American himself, Martin told us the story of Marseilles from a non-white and non-European perspective. He shared some strong opinions with us, some of which resonate within me until now. Martin manifested a great, cross-racial and cross-stereotypical sense of pride mixed with tolerance and pure joy of life. While his perspective honoured the memory of the suffering of millions of people, he uncovered a great deal of hope shattering the perils of staying in the past.

Marseilles’s Panier gave me calmness and comfort that I still feel looking at the photos I took there. There was a distinctive easiness with which the district guided my eye, finger and camera. Panier interacted with the viewfinder seamlessly, almost automatically composing the frames exactly the way I expected them to turn out.

It was a comfortable, perhaps even a soothing experience to be in Panier both on my own, strolling around accompanied only by my Contax, and with the students, giving them my attention and learning about the difficult legacy of colonialism. Another thing I brought to help them explore Marseilles were East German Praktica 35mm cameras. In their own right, they tell another portion of the story of repressions in Europe that finished only in 1990 as they were partly assembled by political prisoners.

To me, someone with limited knowledge of the European Mediterranean, Panier represents the most appealing type of historical district in the region. It bustles with a charming combination of history and present. It is not a tourist-oriented empty shell, left by original inhabitants to make space for money-making machines — deprived of the mundane authenticity of everyday life. Panier still feels real and I as a tourist with my camera felt like a guest, lucky to be welcomed by the community. It made me appreciate the neighbourhood even more and tread carefully on its narrow streets, smiling at my unaware hosts. Panier’s atmosphere also helped me find fellow film shooters and have a relaxed conversation over lunch.

The three days I spent in Marseilles back in 2022 convinced me that the city, especially its Panier district, has at least two flairs. One is for attracting people from all walks of life whose open-mindedness and good will give a sense of a true and intimate community in France’s second largest city. The other one is for telling stories about often tragic and painful developments in a gentle and a peaceful way. Having had the chance to experience it with my Contax was such a dear experience that I came back to it to write this piece.

Marseilles has taught me how to look at a city like a myriad of individual and stories coming together thanks to the hospitable space it offers and the friendly atmosphere it creates. Identifying them often means that you as an educator should only provide a platform to let others speak: after all, their experience and passion are in cahoots with genius loci. For highly engaged students, a bit of contextual knowledge is all what it takes for places like Marseilles to start working its unpredictable yet always marvellously inspiring magic.

My collection of Praktica cameras which I shared with the class was perhaps another reason for my looking fondly at Marseilles and its Panier district. The students appreciated the possibility of shooting film as much as my regular semester class. It is a teaching experiment I mentioned in another story on Medium, co-written with Hannah Wines.

I took all photos used in this story with Contax 139 Quartz and various Carl Zeiss lenses. Please do not use the photos in any way without my consent.

You can find more of my photos here and here.

You can also buy me film to keep my work going.