Over the last months, I have been revising the manuscript of my book on memory politics in post-Soviet Kaliningrad Oblast. While looking at spatial changes in post-1946 Kaliningrad city, which was called Königsberg before that, my eyes turned to Ponarth, the city’s southern suburbs, spared from destruction.

As it often happens, I re-scanned the negatives and reflected upon them instead of pushing the manuscript forward in a more direct way. It is a story of an urban Atlantis in former East Prussia which, although damaged and transformed, continues to live in a sea of growing hatred towards alternative, non-state-sanctioned views at the past of a once multicultural, multiethnic and multi-religious East Prussian oikumene.

In mid- to late 19th century, Ponarth was a true signum temporis. East Prussia, a province of Kingdom of Prussia and, since 1981, German Empire, was predominantly rural, with few towns larger than 5,000 inhabitants. Its capital Königsberg was an exception to this rule. It was created as a fortress during the medieval conquest of pagan Prussians by the Teutonic Knights. The city quickly became a trade outpost located a the Pregel River estuary, as well as a cultural centre. When the last Grand Master Albrecht Hohenzollern secularised the Order and pronounced himself the first duke of Prussia, the ongoing advancement of Reformation fuelled local explosion of religious writing in languages of the believers. Polish and Lithuanian found their way into Königsberg’s university, the Albertina.

The city’s ties with Cracow, Vilnius, Gdańsk and Warsaw in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were stronger than those with Berlin in the Duchy of Brandenburg and, later on, Kingdom of Prussia. The birth of modern European nationalism, however, changed everything. Wars than Prussia fought in 1860s and in 1870s led to the establishment of united and ambitious German Empire. Just like in the case of Italy a decade earlier, although German nation-state was finally created, it still needed its inhabitants to feel a strong bond with this new political entity.

What helped was the railway. Until the early 20th century, mostly rural East Prussia enjoyed dense connections with other parts of the country. It led to mass-scale migration of East Prussians to factories in west Germany. If you are a fan of football, you surely know Borussia Dortmund. The club’s name is nothing less than the Latin name of (East) Prussia.

It was the pursuit for unified German identity that first put the East Prussian microcosm at risk. The push for ethnic, linguistic and cultural unification grew after the First World War when the province was separated from the rest of Germany, becoming a semi-exclave. An area that had always lied at the intersections of different worlds was to exemplify purest Germanness. When Hitler came to power, this axiom overclouded most of the memory of recent heterogeneity of the country’s easternmost province.

But let me come back to Ponarth alone. Industrialisation of the province was selective and mostly affected Königsberg and its surroundings. This is how Ponarth was born. It was the city’s southern suburb, located conveniently by a railway hub. In turn, factories provided fertile ground for the development of residential quarters. In just three decades, Ponarth transformed into a full-fledged, bustling city district as its population rose 18 times — from 450 inhabitants in 1871 to over 8,000 in 1900.

I got interested in Ponarth when I was posted to Kaliningrad as a Polish diplomat. It was the fall of 2020. New wave of covid-19 pandemic was rising. There were not many group activities one could engage oneself in. Taking my camera, staying within the city and walking around was as safe as it was exciting.

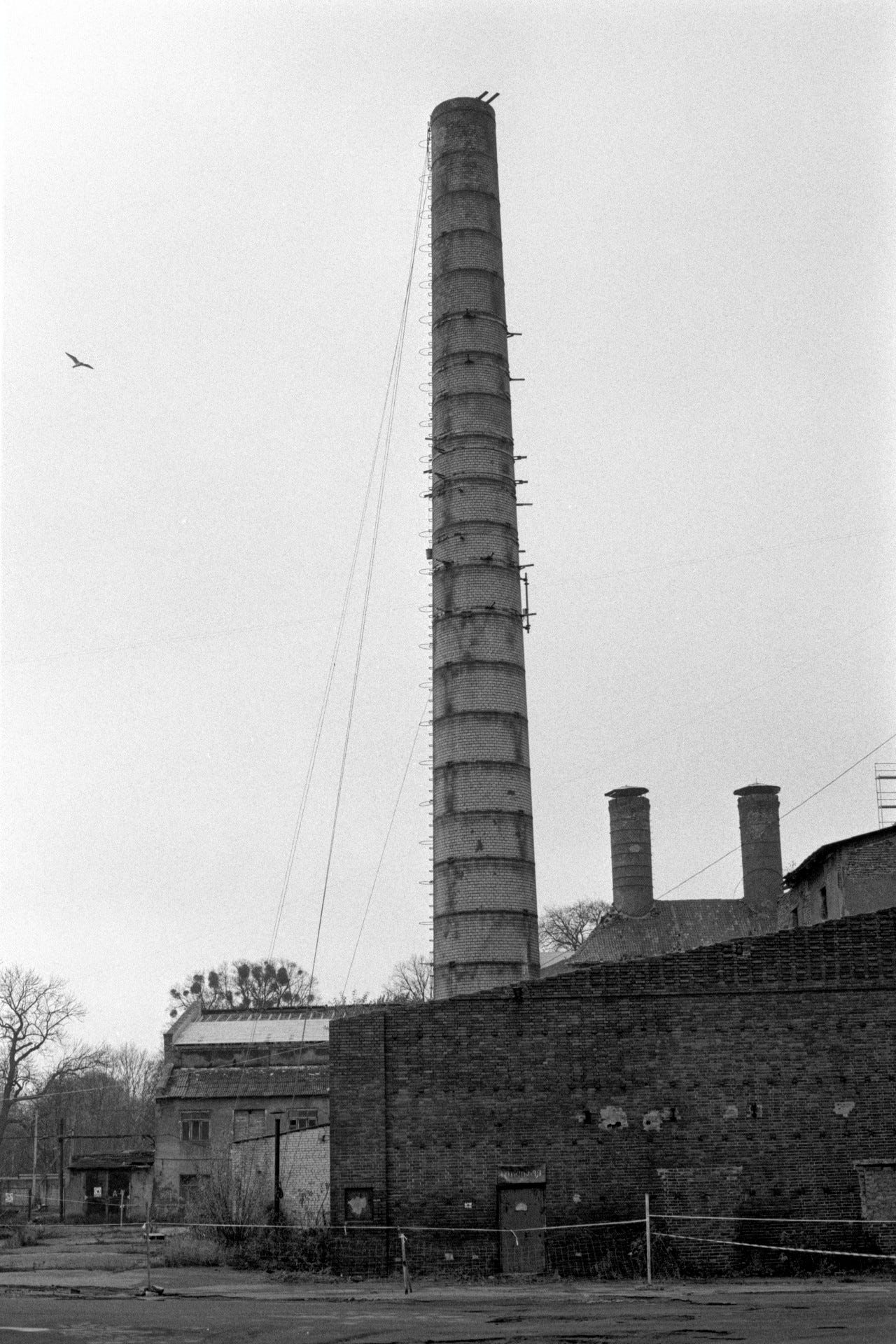

I was amazed by the initial, seeming congruence of pre-war urban planning and the existence of pre-war building with the new Soviet and Russian layer of social life in Ponarth. The moment I got off my car and set foot at a street surrounded by regular and modest brick houses, covered in asphalt with high kerbs and many 20- and 30-year-old cars parked alongside, I knew I was in a place that was not what it seemed.

Seeing Eastern European-style street market opposite a redbrick neo-gothic Protestant-turned-Eastern-Orthodox church, inscriptions in Cyrillic and people wearing typical Russian clothes made me feel odd although I was used to seeing that during the years I had researched identity-related processes in Kaliningrad. I saw discomfort mixed with a feeling of belonging to a place still foreign architecture-wise, developed over merely 75 years of the Soviet and Russian history of this place. Given the fact that Ponarth was founded as a village in the Teutonic Knights times, those three generations accounted for merely one tenth of its existence. And it showed.

In the Soviet reality, churches like the one above could only be spared by using them for non-religious purposes, such as concert halls, theatres, warehouses and houses of culture. When the Soviet Union collapsed and the Orthodox Church entered a formal and increasingly tight relationship with the Russian state, many pre-war building in East Prussia were given to the Church and transformed into places of Orthodox worship. Traditionally, they would have gold-plated (gilded) onion domes which look rather opulent. Adding them to Ponarther Kirche creates a contradiction between the austere Protestant aesthetic and the Eastern Orthodox lusciousness. Look up the interior online and the dissonance will become even greater.

Despite all streets and public places were renamed after the war, it is not uncommon for Ponarth’s inhabitants to use historic names. The name of the district itself proves it.

I decided to write about Ponarth again because of developments in Russia related to memory politics I have been closely following. The material and spiritual legacy of East Prussia, treated with hostility and suspicion already in the Soviet times but spontaneously explored by Kaliningrad Oblast’s inhabitants, has again become an object of criticism due to the shrinking space for grassroots initiatives that do not follow the line set out by the federal authorities somewhere around 2012–2015. It was the time when last mass protests took place across the country. Concerned about their scale, the Kremlin embarked on a series of identity-related policies while crushing any signs of political opposition. We saw a tragic postscript to these processes in mid-February.

The battle over different interpretations of collective memory about what is and used to be Russia has become even more fierce in a region that has been part of the country for merely three quarters of a century. The Oblast is to become a role model for contemporary Russian civilisation which not only protects its canonical territory but also has the vital strength to expand onto what was once part of the Western (German, European, Protestant or Western Orthodox — you name it) civilisation in the Huntingtonian sense of the term.

This logic suggests that places like Ponarth with its eclectic past and present should disappear in one war or another. It could happen by gradual liquidation of objects that still remind the district’s non-Soviet and non-Russian past. It could also mean more traditional Russian architecture, such as white-and-gold Eastern Orthodox churches, museum telling the glorious past of imperial and Soviet Russia and by massive, multi-storey blocks of flats that span all over the country — from Kaliningrad to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy.

In contemporary Russia, space for such small enclaves of modest diversity as Ponarth is shrinking dramatically. Does it mean that the tension between the past that has not disappeared entirely and presence that is becoming increasingly oppressive will ease? I doubt it. Oftentimes top-bottom attempts to accelerate the natural apace of assimilation with and internalisation of new cultural surroundings lead to feeling of belonging even less.

The principal question is how to come to terms with the fact that the dominating role of the Russian language and culture is still a new phenomenon from the perspective of the last 800 years. Russia’s current political regime might change at some point but how will it affect situation on the ground in Kaliningrad? Will new federal authorities see a value in the remaining traces of diversity of a region that had once been full of different tongues, religions and ethnicities?

I intend to come back to these questions in a different story, this time about the village of Pribrezhnyi not far away from Kaliningrad. There, Soviet times star at you from every corner in a depressing way. In Pribrezhnyi, you can see that the pre-1945 humble rural reality of East Prussia feels like a surprisingly attractive reference point given the level of contemporary decay. Just 25 kilometres from the border of the European Union, it is a strikingly accurate sample of where things stand in today’s Russia.